Copyright © 2008 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 54, No 4 - Winter 2008

Editor of this issue: M. G. Salvėnas

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2008 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 54, No 4 - Winter 2008 Editor of this issue: M. G. Salvėnas |

Narratives of Identity: A

Postcolonial Rereading of Dalia Grinkevičiūtė’s

Lithuanians by the

Laptev Sea

Jerilyn Sambrooke

Jerilyn Sambrooke is a Ph.D. candidate in Comparative Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Previously she lectured at Fatih University in Istanbul, Turkey, and at LCC International University in Klaipėda, Lithuania. Her research interests focus on the application of postcolonial theory to the Baltic states and other regions not traditionally considered.

Abstract

Postcolonial scholarship has not yet paid much attention to the Baltic

States, but it is an emerging phenomenon. This paper attempts to

demonstrate that Eastern Europe, specifically Lithuania, is a

postcolonial place, and that postcolonial discourse opens up

possibilities for new readings of the recent – and painful

– past. Using Dalia Grinkevičiūtė’s

autobiographical narrative Lithuanians by the Laptev Sea, which

recounts her family’s ordeal during the mass deportations of

Lithuanians to Siberia in 1941, the paper argues that postcolonial

theory challenges common approaches to the text as it is read

throughout Lithuania. Working with Homi Bhabha’s conceptions

of history in The Location of Culture (1994), the paper suggests that

painful experiences in Lithuania’s recent past, such as the

deportations of 1941, are best read as continually shaping and

reshaping the present culture of Lithuania, rather than read as

departure points out of which the Lithuanian nation-state has been

created.

The effort of Lithuanians to articulate and assert a collective identity has encountered strong – and often violent – resistance in the recent past of Soviet oppression. Because Lithuania is well into its second decade of independence, contemporary expressions of identity struggle with the question of how to address this history of oppression. Dalia Grinkevičiūtė’s famous autobiographical account of the 1941 deportations to Siberia provides a fascinating case study of the dialogues around contemporary Lithuanian identity. The present article draws on prevailing current readings of Grinkevičiūtė’s text and re-examines them within the framework of a growing discussion about the relevance of post-colonial theory for literature from post-Soviet countries. While the traditional reading tends to focus on the authenticity of the eyewitness account and links the text to Lithuania’s political independence, this article, drawing on a widening discussion about the relevance of postcolonial theory to literature from post-Soviet countries, argues that postcolonial theory, specifically the work of Homi Bhabha, makes it possible to view Grinkevičiūtė’s narrative of deportation in a new light.

Rather than restricting it to an act of merely documenting past atrocities, which distances the reader from those events, Bhabha’s work emphasizes the role that the past has in shaping the identity of the author as well as that of her contemporary readers. The question for this article, simply stated, is: How can postcolonial discourse open discussions about the difficult – and recent – experiences under the Soviet regime in order to understand more fully contemporary Lithuanian identity?

The problematic relationship between postcommunism and postcolonialism must be acknowledged, however, before advancing the larger argument. Present resistance to the inclusion of post-Soviet states in the umbrella group of postcolonial states has come from academics in post-Soviet as well as postcolonial studies. Violeta Kelertas, in her introduction to the collection of essays Baltic Postcolonialism (2006), which she edited, recognizes the resistance to postcolonialism as it relates to the Baltic States; the very publication of the volume offers an argument against the false division of the areas of study. In various ways, each of the authors published in the collection addresses this resistance. Some scholars, like Almantas Samalavičius, state that much of the resistance to postcolonial theory comes from scholars within the academic community in post-Soviet states:

Efforts to synchronize its [Lithuanian academic criticism’s] orientation with contemporary trajectories of analysis [i.e., postcolonialism] are judged by the institutional critics as polemics of little merit or ideologically dangerous heresies.1

This resistance is further compounded by the reluctance of the postcolonial academic community to engage post-Soviet states themselves in their theoretical dialogue.

Romanian literature scholar Adrian Otoiu offers an explanation why a sustained, meaningful dialogue between post-Soviet and postcolonial scholars has been so slow to emerge. Otoiu comments on the difficulties he encountered to gain a hearing at postcolonial academic conferences: “My appeal for a dialogue that should include issues relevant to the postcommunist world was met with a shrug or a frown.” 2 His subsequent investigation led him to conclude that postcolonial academics were resistant to changing what appears to be a scripted exchange between the colonized and the colonizing while resistance from within the post-Soviet states is largely due to each state wanting to assert its unique national identity rather than to identify with a collective postcommunist group of states with which they had never strongly identified before.

David Moore offers another perspective on the question.3 Moore argues that almost all groups of people have been both conquerors and the conquered at various times in history and could, therefore, all fruitfully be considered as “postcolonial.” The postcolonial approach then becomes comparable to a Marxist analytical approach (which the academic community seems comfortable applying across diverse historical contexts). Moore finds the current definition of what qualifies as postcolonial to be unnecessarily limiting, and he challenges scholars in both postcommunist and postcolonial studies to question their assumptions, thereby opening the possibility to consider post-Soviet nations as postcolonial.

Returning to Samalavičius and the Baltics, Samalavičius insists, as do some others, that Lithuania must be understood as postcolonial:

…if the past is not understood as a protracted and conscious colonization executed by an exterior power (i.e., the Soviet Empire), it is impossible to adequately evaluate the habits of thought and social activity, as well as the pathologies of self-identification formed during that period, which, though they were not as obvious as those in the societies of the so-called ‘Third World,’ left their imprint not only in Lithuania but in the other Baltic States as well.4

Samalavičius makes an effort to define the Soviet oppression as “protracted and conscious” colonization, arguing that only when Lithuanians see their history as colonization will they be able to analyze more effectively the impact of the past on their contemporary life. The implied distinction that Samalavičius makes between “colonization” and “occupation” is one that often rises to the surface during discussions in which “postcolonial” is deemed inapplicable to post-Soviet states.

Discussions along the traditional lines demand that the experience of any given country be matched with a certain kind of postcolonial prototype. Accordingly, the theory may be applied only if there is an acceptable match. If the match is deemed unacceptable, then the theory may not be accurately applied. Bill Ashcroft shifts the terms of this discussion significantly, which is very helpful when considering how postcolonial discourse is relevant for the Baltics and, more specifically, to Grinkevičiūtė’s memoirs. Ashcroft argues that the specifics of a historical experience – of events and facts – are no longer what identifies postcolonial locations. As the term postcolonial is applied to a myriad of histories or “experiences,” extending beyond the traditional realm of the “postcolonial Third World,” theorists have been forced to more precisely reconsider what characterizes postcolonial cultures. Ashcroft follows the lead of Arif Dirlik, who argues that since postcoloniality no longer is seen to apply exclusively to the context of the Third World, the identity of the postcolonial is no longer structural or geographical but rather discursive. Building on this distinction, Ashcroft contrasts “forms of experience” and “forms of talk about experience.” This definition frees academics from proving that the experiences of these postcolonial nations share a common essence, which appears to be the focus for many of the approaches considered earlier. Of course, it must be acknowledged that there is no one list of experiences or atrocities that qualify a nation to be categorized as “postcolonial.” Instead, the focus is directed to the discourses that surround the diverse histories, drawing attention to the dialogue that is occurring between different modes of resistance.

This paper investigates how Dalia Grinkevičiūtė’s memoirs talk about experiences of oppression, demonstrating that Homi Bhabha’s postcolonial theory offers a valuable framework in which narratives of deportation can be reconsidered.

Introduction to Grinkevičiūtė’s Text

Dalia Grinkevičiūtė’s entire family was exiled to Siberia in June, 1941, during the early years of World War II. The Non-aggression Pact of 1939 between Stalin and Hitler made provisions for the expansion of Soviet influence into Lithuania. When the Soviets invaded Lithuania in 1940, they planned large deportations of the local population in an attempt to establish and maintain authority in the region. These deportations began in June of 1941, and Grinkevičiūtė’s family was among the 17,000 Lithuanians who were sent to various concentration camps across Russia. The deportations were cut short when Hitler broke his pact with Stalin and himself marched his army into Lithuania on June 21, 1941.

Grinkevičiūtė’s father was sent to a concentration camp in the Northern Urals and died after two years of starvation and overwork. She, along with her mother and brother, were sent to a collective farm, then to a work camp in the far North, and finally to an uninhabited island 800 kilometers beyond the polar circle. From 1941 to 1949, Trofimovsk Island was used as a concentration camp, and few inmates survived. Grinkevičiūtė’s memoirs recount the horrors of life at Trofimovsk.

The memoirs themselves have a long and complicated history. She wrote the first version of her memoirs around 1950, after sneaking back into Lithuania from exile. Since she had entered the country “illegally,” she had to hide her writings, burying them in the ground in a glass jar. She was unable to return to them during her own lifetime, and this manuscript was discovered only in 1991 and subsequently published in Lithuanian in 1997 (reprinted in 2005), and in English in 2002. Grinkevičiūtė continued to write throughout her life, however, and wrote other versions of her deportation experience.8 This article focuses primarily on the Lithuanian version of the memoirs that appeared in 1988 in the journal Pergalė. This later version, which is shorter and more focused, has also been translated into Russian and English. Since this article will refer to both versions of the text, they will be referred to as the earlier version – written in 1950 (published in 1997) – and the later version – written in the 1970s (published in 1988).

The political and social context of this first Lithuanian publication has strongly influenced the reading of Grinkevičiūtė’s memoirs, both in 1988 and still, to some extent, today. In 1988, Lithuania was in turbulent transition, moving towards its official declaration of independence in 1990, and it was in this context that the memoirs were published and, significantly, given a title. Grinkevičiūtė herself had not titled her manuscript, and since the text was published posthumously in 1988 (she died in 1987), it was the publishers who chose the title “Lithuanians by the Laptev Sea.”9 Literary critic Jūra Avižienis argues that the inclusion of “Lithuanians” in the title encouraged readersto view the text as a statement of a shared national experience of oppression:

The title nationalized the experiences…and elicited a particular kind of reading during the years leading to and immediately following Lithuanian independence….it demanded that the memoirs be read as a statement about how Lithuanians as a national group were treated and impacted by Soviet occupation, and it denounced Soviet incorporation by Lithuanians as a national entity.10

By encouraging the Lithuanian reader to identify with the text along national lines, the publishers were contributing to the larger narrative of independence forming in Lithuania at the time. The deportations were framed as an example of Soviet treatment from which all Lithuanians should now work to free themselves.

Some recent criticism surrounding this text continues to echo this emphasis on national identity. In 2002, an English translation of the earlier memoirs (the version that was buried in 1950) was published with an introduction by the prominent politician Vytautas Landsbergis. Landsbergis was a key leader in the Lithuanian independence movement, later becoming the first leader of independent Lithuania. Both the editor’s choice to have such a prominent political figure introduce the text and his specific comments illustrate that the nationalized reading of the text still persists.

In the reading of Grinkevičiūtė’s memoirs that Landsbergis offers, the text is seen as offering the true version of what happened. The value of the text lies primarily in its authority as an eyewitness account. It ought to be given social and political prominence, he suggests, because it legitimately challenges the previous Soviet suppression of discussion surrounding the deportations. Landsbergis begins his introduction with a bold, direct statement about Grinkevičiūtė’s intent to document the truth: “Dalia Grinkevičiūtė’s mission was to testify about what happened.”11 To testify about what happened means, for Landsbergis, to bring into the open the facts of the atrocities the Soviet regime committed against the Lithuanian deportees.

Secondly, Landsbergis encourages the reader to interpret the text as an exemplary case study of how Lithuanian courage endures in the face of Soviet oppression. He frequently draws attention specifically to the national identity of the deportees, encouraging his readers to wonder at the admirable struggle for survival and hope among these Lithuanian deportees: “There were a great number of deportees in the North. The songs of Lithuanians could be heard along the banks of the Angara in Siberia…. ‘Let me go back to my homeland’ became the anthem of the deportees.”12 National song is a strong tie in any culture, perhaps especially in the Baltic States, and Landsbergis is deliberately encouraging his readers to see the attachment of the deportees to the nation of Lithuania. He is also encouraging his Lithuanian readers to identify emotionally with the Lithuanian deportees, reminding his readers that they share the same songs.

This reading of the narrative, however, implies a cause and effect logic of history that is problematic. While I would not go so far as to say that Landsbergis is incorrect in his reading of the text (Grinkevičiūtė does include very detailed information about what happened), the focus on the historical and national nature of the deportation results in an incomplete reading. The text is seen to give a departure point from which Lithuanians now move. The text becomes a “cause,” representing the deportations and violence of the Soviet regime, against which contemporary Lithuanians are encouraged to react. By supporting an independent, free Lithuania, in which such deportations would never again occur, one is seen as responding appropriately to the violence of the past. If the deportation is the “cause,” then a free Lithuania is the “effect.” Grinkevičiūtė’s text, then, is useful in as far as it furthers the political agenda of an independent Lithuania, but the experience of deportation is then subjected to this narrowly functional reading. All details of the experience that do not relate to this political narrative are forgotten, or at least deemed less significant. The logic of cause and effect simplifies both the experience of deportation and the role of the narratives in the Lithuanian community. Reading the memoirs as a statement of national identity – as was done both at the time of their publication in 1988 as well as in current discussions – encourages Lithuanian identity to be developed by using the Soviet past as a departure point along a chronological timeline towards independence.

Other recent critics have developed creative new readings of the text,13 but in discussion of such deportation narratives, there still is often an assumption that the value of the narratives lies in their ability to give expression to the deportation as it was truly experienced. This assumption, arguably, places artificial barriers around the text and its meaning.

Viktorija Daujotytė also suggests that this emphasis on documentation and truth-telling limits the potential of the text:

Documentation is an important feature of her texts, but no less important are other features, like the aspects of the writing that relate to the quality of the texts, and a phenomenally down-to-earth participation of the writer in the narrative structures. The text is based on dialogue; it conveys creativity and a striving for one’s language (including that of the narrator) to connect with the thoughts and words of others.14

Daujotytė goes on to trace the intersection of the text with existential philosophy and the writings of Grinkevičiūtė’s contemporaries, and she suggests that rather than focusing on documenting atrocities, Grinkevičiūtė seems to focus on an attempt to look beyond oneself and to understand others. Like Daujotytė, the present article also attempts to see what lies beyond the text when the dominant model is no longer “testimony” or “truth-telling.” Specifically, I will focus on Grinkevičiūtė’s later version, suggesting that it is a postcolonial understanding of identity that emerges.

To make this shift and focus on the explorations of identity that are present in the text, I return to postcolonial theory and Ashcroft’s distinction between “forms of experience” and “forms of talk.” In the case of Grinkevičiūtė’s narrative, I suggest that we need to move away from emphasis on what happened to her in exile and instead focus on how she articulates these experiences. Analysis of the later version (1988) of her memoirs reveals that the text consistently returns to the question of identity. Her concern is to testify not only to the events as she experienced them but, even more significantly, to probe how those events have served to shape her identity. To go one step further, the argument can be made that these events are narrated in a style that also challenges the reader to consider how his or her identity is impacted.

Turn to Postcolonial Theory

The work of Homi Bhabha is particularly helpful when analyzing how postcolonial theory draws attention to a form of talk rather than a form of experience. He consistently argues that that “post”colonial means “ beyond“ rather than “after”. This distinction, while at times vague, is helpful in that it encourages a critic to see how a text is speaking through the colonial experience. The discourse as encountered in the present is constantly in dialogue with the past. In moving beyond the colonial past, one never departs from that past.

Bhabha argues that it is in the works of art that are produced on the periphery of a culture – by the transients, the migrants, the marginalized – where one most clearly sees how an artist is able to move “beyond” or “through” the colonial experience without ever departing from it. The creative act does not reject the past, but rather brings it into the present:

The borderline work of culture demands an encounter with ‘newness’ that is not part of the continuum of past and present… Such art does not merely recall the past as social cause or aesthetic precedent; it renews the past, refiguring it as a contingent ‘in-between’ space, that innovates and interrupts the performance of the present.15

If the past is not simply the social cause for a text but rather works to interrupt the performance of the present, then it becomes possible to interpret Grinkevičiūtė’s memoirs as more than a statement defining Lithuanian identity in opposition to Soviet mistreatment. She is calling the past – the experiences of deportation – into the present, providing insight for the reader on how these experiences have shaped her as narrator. The narrative voice and the structure of the text also create the effect of posing this question of identity to the reader. By drawing the past into the present in this manner, the reader is challenged to acknowledge that, like Grinkevičiūtė, the reader herself/himself never departs from that past but instead also must move through it.

Bhabha develops this idea of the past interrupting the present in a more concrete way as he looks at the notion of “home” in various literary works. “Home” is perceived to be a place of stable identity, where one has been and is understood. In cultures experiencing oppression, home is also often linked to a very positive version of the past—a life before oppression. In Grinkevičiūtė’s case, home is understandably tied to freedom. Referring to several works of postcolonial literature that problematize the idea of the stable home, Bhabha develops the notion of the “unhomely” to capture the instability of home and of the past. A closer look at Grinkevičiūtė’s narrative shows that home and the past are not as stable as even she would like them to be.

The word “unhomely” is a deliberately awkward translation of the original German “unheimlich,” which is a tidy opposite of “heimlich,” or “homely”. In developing these concepts, Bhabha suggests that this space between the “heimlich” (homely) and “unheimlich” (unhomely) is a postcolonial place, a space in which one sees how a person’s identity is a complex mixture of what is foreign and what is familiar. Layered on top of this tension between the foreign and familiar is the second, more common, translation of “unheimlich” as “uncanny,” echoing the work of Sigmund Freud. Just as the subconscious subtly creeps into the conscious, creating an uncanny moment, so the world creeps into the home, destabilizing an identity that was thought to be secure. In his essay “The World in the Home,” Bhabha defines the unhomely moment as “the shock of recognition of the world-in-the-home, the home-in-the-world”.16 In this moment of shock, the personal, stable space of the home is invaded by wider political realities.

This shock of recognition – an experience of alienation from what one thinks is familiar – is generally considered to be negative. Alienation is, after all, usually a very painful experience. Bhabha, however, is suggesting that the alienation that one experiences in the “unhomely moment,” may also present an opportunity – an opportunity to reevaluate one’s identity:

If the uncanny is homely, what is close to home, it none the less has a tendency to morph into the profoundly unfamiliar, the unhomely, which estranges us from what we thought was most properly our own. Alienation would usually be thought of as a problem, but if it is something which is part of all experience, and is even something which might inspire us to reevaluate our identities, then we can understand it as an opportunity. The uncanny, in other words, opens a space for us to consider how we have come to be who we are.17

It is certainly a difficult task to reevaluate one’s identity in response to an experience of alienation, but this is exactly what Grinkevičiūtė does as she writes of her deportation experience. In the later version of her memoirs, she develops a narrative voice and structures the narrative in ways that clearly evidence a recognition of how her identity has emerged in dialogue with her past.

Narrative Voice

It is specifically Grinkevičiūtė’s narrative voice that opens the possibility for reading the text as a struggle of identity. As an autobiographical piece of writing, the narrator, the main character, and the author all claim to be the same individual, and yet are distanced from one another as they exist in different moments of time. By moving throughout the text between the “I” who is the autobiographical writer and the “I” who is the young exiled girl of fourteen, Grinkevičiūtė creates a gap. While this gap could be seen as a basic feature of any autobiographical writing, Grinkevičiūtė deliberately draws attention to the voice of the narrator by interrupting the flow of the past-tense narrative with instances of the present tense. These interruptions in the present tense have, arguably, two effects. First, they push the reader to acknowledge that the experiences of the past continue to define the present for the narrator. Secondly, these moments invite the reader – who now occupies this present space with the narrator – to see how the past defines the reader’s own identity in the present.18

Of the several instances of tense changes, this paper will highlight only three. One of these changes in tense occurs during the description of the awful polar nights of constant darkness, during which many deportees died. Sick with scurvy, many deportees could not stand up to relieve themselves and were forced to lie in their own excrement. Lice infested even their eyebrows and eyelashes. “The end seemed imminent”19 does not sound overly dramatic as a summary of the situation. Into this hopelessness arrived Doctor Samodurov. For a month he worked to help the prisoners simply survive by negotiating food rations, opening the bath house, and using the disinfection chamber. It was a turning point in the lives of those deportees: “After a month Doctor Samodurov left. We heard that he had been killed at the front, but then, maybe that wasn’t true? We all bow to you, Doctor Samodurov.”20 Who, exactly, is bowing to the doctor? Implied in the “we” are those who were saved by his work. However, the present tense complicates the use of “we” in that way, since many of that group would have already died by the time of writing. Perhaps Grinkevičiūtė means simply those prisoners who were still alive, as she was.

I would like to suggest a broader interpretation: she and her readers bow to the doctor. All those who are thankful for what he did – the “we” who join her in the act of telling and of reading the story – these are the ones who bow. Grinkevičiūtė seems to invite the reader of her text into this process of identification with the past. Rather than “acknowledging” the past, which allows a person to see the event as it “truly was” and then act on it, the reader is being asked to see how these experiences continue to effect the narrator and, by extension, the reader. These events haunt the writer, and the narrative seems less concerned about “telling the truth” of what happened (did the doctor really die?) and rather more concerned about inviting the reader to allow himself/herself to be haunted by these events as well.

The second example of a change of tense in the narrative voice is taken from the end of the first section. The narrator tells in the present tense of the burden she feels for the deportees: “The dead continue to live in my heart. Many years have passed but I can still see them… It is my duty to tell their story.”21 In her inability to push these people from her mind, she recognizes that she cannot forget the past but rather must continually retell it, bringing it into the present:

For those who died at Trofimovsk, the only way back to their homeland is through Grinkevičiūtė as a writer. As Grinkevičiūtė invokes the presence of the wandering dead, she finds herself spanning the distance between Lithuania and Trofimovsk Island. The “I” who knows those people wanders with them, and recognizes that her identity is only able to be understood in the context of this wandering. By narrating these events in the present, she pushes her audience, her readers, not only to react against these events in the past, but, more significantly, to see how this wandering among the dead is shaping their identities in the present.

Unhomely

These examples of the past interrupting the present occur in the first section of Grinkevičiūtė’s memoirs. In the second section, the narrative layers another instance of the present tense with a specific reference to the present in Lithuania. In Section Two, the memoirs quickly span the summer of 1943 through to the winter of 1949, the year of Grinkevičiūtė’s escape with her mother back to Lithuania. Grinkevičiūtė skips right over the drama of the escape and the long-awaited return to Lithuania and focuses much more on the illness and death of her mother. Her mother’s longing to be buried in Lithuanian soil is what demanded that they return quickly to Lithuania that winter. Once there, she recovered briefly, but then her health declined again rapidly. As she became aware of her impending death, she specifically requested that they return to their original home in Kaunas.

This return home becomes the central focus of the second section of Grinkevičiūtė’s narrative. As the concentric circles become progressively smaller and the two women return closer to their original place of departure, they become increasingly nervous about being found out. The danger of returning to their apartment in Kaunas is very real. The risk of being sent back into exile is even greater after the death of her mother. How do you bury a woman who has entered the country “illegally”? After rehearsing the various burial scenarios with the reader (the longest section of text that the reader has yet encountered on a single concept in this fast-moving section), Grinkevičiūtė comes to realize that there may be no place for her mother in her own homeland: “Could it be that there really is no room for my deceased mother in our native land? In the cellar there is a little area that was meant to be used as a hiding place in case of war. I will bury her there.”23 Grinkevičiūtė recounts in detail how she is able to create a grave and lower her mother into it. At one point, as she is picking away at the thick layer of cement, she even humorously comments that “father did not realize when he was building the house how difficult it would be to knock out a grave for mother here.”24 She finally succeeds in burying her mother in the cellar and then covers all traces of the grave.

Grinkevičiūtė concludes this second section of the narrative with another incidence of the use of the present tense: “Unknown graves… How many of them there were and still are in Lithuania…”25 This final sentence functions as a cadence at the end of the long struggle to put her mother to rest. The statement first serves to generalize her mother’s grave (how many graves are like her mother’s – hidden in their own home?), and second, it reminds the reader that this past experience remains relevant to the present (these graves are still hidden throughout the Lithuania of 1988). Here again, Grinkevičiūtė is inviting the reader to acknowledge with her how the past continually interrupts the present, and in this case, it is the political events of the larger world that are interrupting the most private, personal moments of the death and the burial of a mother.

Conclusion

As discussed above, the unhomely moment is characterized by the morphing of the familiar into the unfamiliar, a moment of distancing from what one previously thought to be one’s own. In returning to Lithuania and daring to return to the home that the family had built, both Dalia and her mother know that they are entering a sphere of increasing danger rather than a safe return home to rest. The secret grave in the cellar becomes a symbol of the rejection of Grinkevičiūtė’s mother by her homeland.

Can one, however, argue that this unhomely moment in Grinkevičiūtė’s text is more than just painful alienation from her home country and her own home in Kaunas? To use David Huddart’s words, is there an opportunity here to “consider how we have come to be who we are”?

Significantly, Grinkevičiūtė’s use of the present tense in this later 1988 version of her memoirs is one key indication that she has written these memoirs as a way to work out how her own identity has been influenced by her experiences during deportation. In the act of writing, and in the decision to engage the present tense at key points throughout the text, she is most certainly pausing to consider who she has become as a result of these experiences. In addition to her concern for her own story, however, she also reminds the reader that her experiences have impact far beyond her. The history of oppression and deportation is continually resurfacing in private and personal spaces, and this history is making itself felt in continually new moments, including each moment in which Grinkevičiūtė’s memoirs are read.

WORKS CITED

Ashcroft, Bill. Post-colonial Transformations. London: Routledge, 2001.

Avižienis, Jūra. “Learning to Curse in Russian: Mimicry in Siberian Exile.” In Kelertas, 2006.

_____. “Mediated and Unmediated Access to the Past: Assessing the Memoir as Literary Genre.” Journal of Baltic Studies. 2005, Vol. 36, No. 1, 39-50.

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994.

_____. “The World and the Home.” Social Text. 1992, Vol. 10, No. 31.

Daujotytė, Viktorija. “Kelyje į Literatūros Lobyną.” In Grinkevičiūtė, 2005.

Edwards, Brent Hayes. “The Genres of Postcolonialism.” Social Text. 2004, Vol. 22, No. 1 (78), 1-15.

Gostautas, Richard. “Exile and Imprisonment Locations of the Residents of Lithuania (1941).” Lithuanian Genealogy Database. Richard Gostautas. 20 May 2006. <http://www.lithuaniangenealogy.org/databases/lithuania/exile/index.html?letter="E">

Grinkevičiūtė,

Dalia. Lietuviai prie

Laptevų jūros: atsiminimai miniatiūros. 2nd

edition. Vilnius: Lietuvos Rašytojų Sąjungos Leidykla, 2005.

_____. A Stolen Youth, A

Stolen Homeland: Memoirs. Trans. Izolda

Geniūšienė. Vilnius: Lithuanian Writer’s Union,

2002.

_____. “Lithuanians by the Laptev Sea: An Excerpt From a Memoir.” Trans. Laima Sruoginis. In: Sruoginis, 2002.

_____. “Lithuanians by the Laptev Sea: The Siberian Memoirs of Dalia Grinkevičiūtė.” Trans. Laima Sruoginytė. Lituanus: Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences. 1990, Vol. 36, No. 4 and <http://www.lituanus.org/1990_4/90_4_05.htm> Accessed April 24, 2008.

Huddart, David. Homi K. Bhabha. London: Routledge, 2006.

Kelertas, Violeta, Ed. Baltic Postcolonialism. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006.

Kiaupa, Zigmas. The History of Lithuania. Trans. S.C. Rowell, Jonathan Smith, and Vida Urbonaičius. Ed. S.C. Rowell. Vilnius: Baltos Lankos, 2002.

Kurvet-Käosaar, Leena. “Imagining a Hospitable Community in the Deportation Narratives of Baltic Women.” Prose Studies. 2003, Vol. 26, No. 1-2, 59-78.

Landsbergis, Vytautas. “Introduction: A Piercing Light.” In Grinkevičiūtė, 2002. 26 >

Otoiu, Adrian. “An Exercise in Fictional Liminality: the Postcolonial, the Postcommunist, and Romania’s Threshold Generation.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. 2003, Vol. 23, No. 1-2, 87-105.

Samalavičius, Almantas. “Lithuanian Prose and Decolonization: Rediscovery of the Body.” Trans. Violeta Kelertas. In Kelertas, 2006.

Sruoginis, Laima, Ed. The Earth Remains: An Anthology of Contemporary Lithuanian Prose. Vilnius: Tyto alba, 2002.>

|

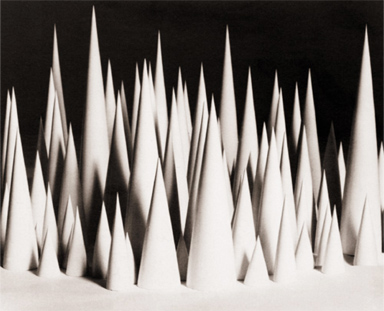

| Elena Gaputytė, "Beyond the Arctic Circle

– In Memory of the Victims of Trofimovsk", installation, 1989–1990. |